Introduction: The Importance of Gastrointestinal Motility

As we observe Constipation Awareness Month 2025, it is essential to move beyond the discomfort associated with the condition and understand the underlying biological mechanisms governing gut health. Constipation is not merely a transient inconvenience; it is a clinical manifestation of altered gastrointestinal (GI) physiology, specifically affecting the large intestine (colon).

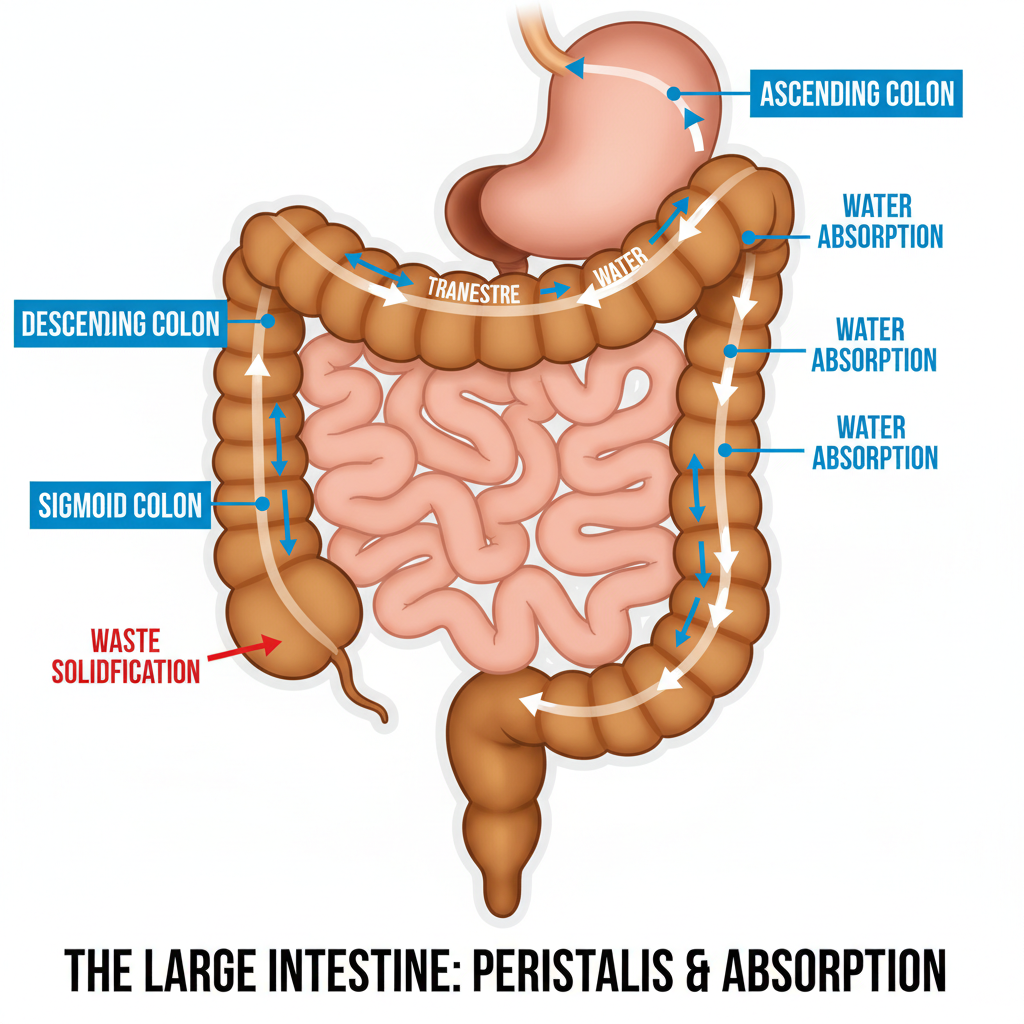

Biologically, the primary function of the colon is the reabsorption of water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter and the formation of solid waste for excretion. When this process is disrupted—either through delayed transit time or dysfunction in the neuromuscular coordination of the bowel—the result is constipation. Understanding these mechanisms is the first step toward effective management and prevention.

2. The Physiology of Digestion and Motility

To understand why constipation occurs, one must understand peristalsis. This is the series of wave-like muscle contractions that moves food through the digestive tract.

In a healthy system, chyme (partially digested food) enters the cecum from the small intestine in a liquid state. As it traverses the colon, epithelial cells lining the lumen absorb water and salts. If the transit time—the duration waste spends in the colon—is optimal, the stool remains soft yet formed.

However, if colonic transit time is prolonged, the colon absorbs an excessive amount of water. This desiccation leads to hard, dry stools that are difficult to pass. This relationship can be modeled conceptually:

$\text{Stool Consistency} \propto \frac{1}{\text{Transit Time}}$

As transit time increases (slows down), consistency decreases (becomes harder).

World AIDS Day 2025: Understanding HIV Early Symptoms, Risks & Prevention for a Safer Future

3. Etiology: Causes and Risk Factors

Constipation is generally categorized into two types: primary (functional) and secondary (caused by underlying conditions or medications).

3.1 Functional Causes

Functional constipation often stems from lifestyle factors that disrupt the gastrocolic reflex, the physiological signal that stimulates colonic motility after eating.

Low Dietary Fiber: Fiber increases stool bulk. According to physical laws governing tension (Laplace’s Law), increased bulk stretches the colon wall, stimulating mechanoreceptors that trigger stronger peristaltic contractions.

Dehydration: Water is essential for maintaining the osmotic balance within the bowel lumen. Without sufficient fluid, the colon aggressively reabsorbs water to maintain systemic hydration, drying out the stool.3.2 Secondary Causes

Medications: Opioids, calcium channel blockers, and anticholinergics inhibit smooth muscle contraction in the gut.

Metabolic Disorders: Conditions like hypothyroidism ($T_3/T_4$ deficiency) slow down the body’s metabolic rate, including gut motility.

International Day of Persons with Disabilities 2025: Why Inclusive Healthcare Matters More Than Ever

4. Symptomatology and Assessment

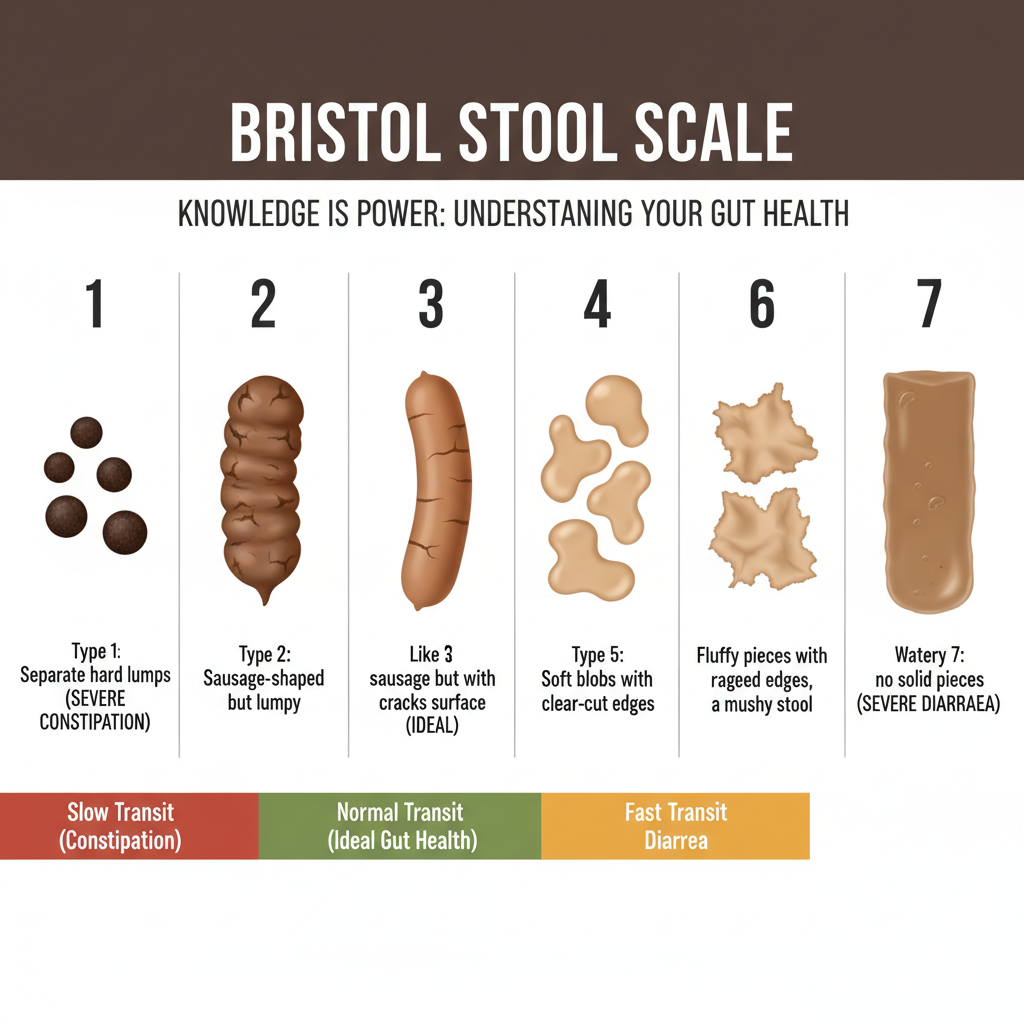

Clinicians often use the Rome IV Criteria to diagnose functional constipation, but for patient education and self-monitoring, the Bristol Stool Scale is the standard visual tool.

- Type 1 & 2: Indicate slow transit (constipation).

- Type 3 & 4: Indicate normal transit (ideal gut health).

- Type 5, 6 & 7: Indicate fast transit (diarrhea).

Symptoms often extend beyond the bathroom. Due to the gut-brain axis—the bidirectional communication between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system—chronic constipation can lead to systemic symptoms such as fatigue, irritability, and bloating.

5. Daily Habits to Improve Gut Health

Optimizing gut health requires a multimodal approach focusing on diet, hydration, and physical mechanics.

5.1 Dietary Fiber Optimization

Fiber is the substrate for the microbiome. Fermentation of soluble fiber by gut bacteria produces Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which serve as fuel for colonocytes and regulate motility.

Target: The recommended daily intake is approximately $25\,\text{g}$ to $30\,\text{g}$ for adults.

Sources: Legumes, whole grains, fruits (with skin), and vegetables.

5.2 Hydration Kinetics

Fiber acts like a sponge; it requires water to function. Increasing fiber without increasing water can exacerbate constipation.

A general estimation for daily water requirement ($V_{\text{water}}$) for a healthy adult can be approximated by body mass ($m$):

$V_{\text{water}} \approx 35\,\text{mL} \cdot \text{kg}^{-1} \times m$

For a $70\,\text{kg}$ individual:

$V_{\text{water}} \approx 35\,\text{mL} \cdot \text{kg}^{-1} \times 70\,\text{kg} = 2450\,\text{mL} \approx 2.5\,\text{L}$

5.3 Physical Activity and Mechanics

Exercise: Aerobic activity increases blood flow to the GI tract and stimulates the smooth muscles of the colon.

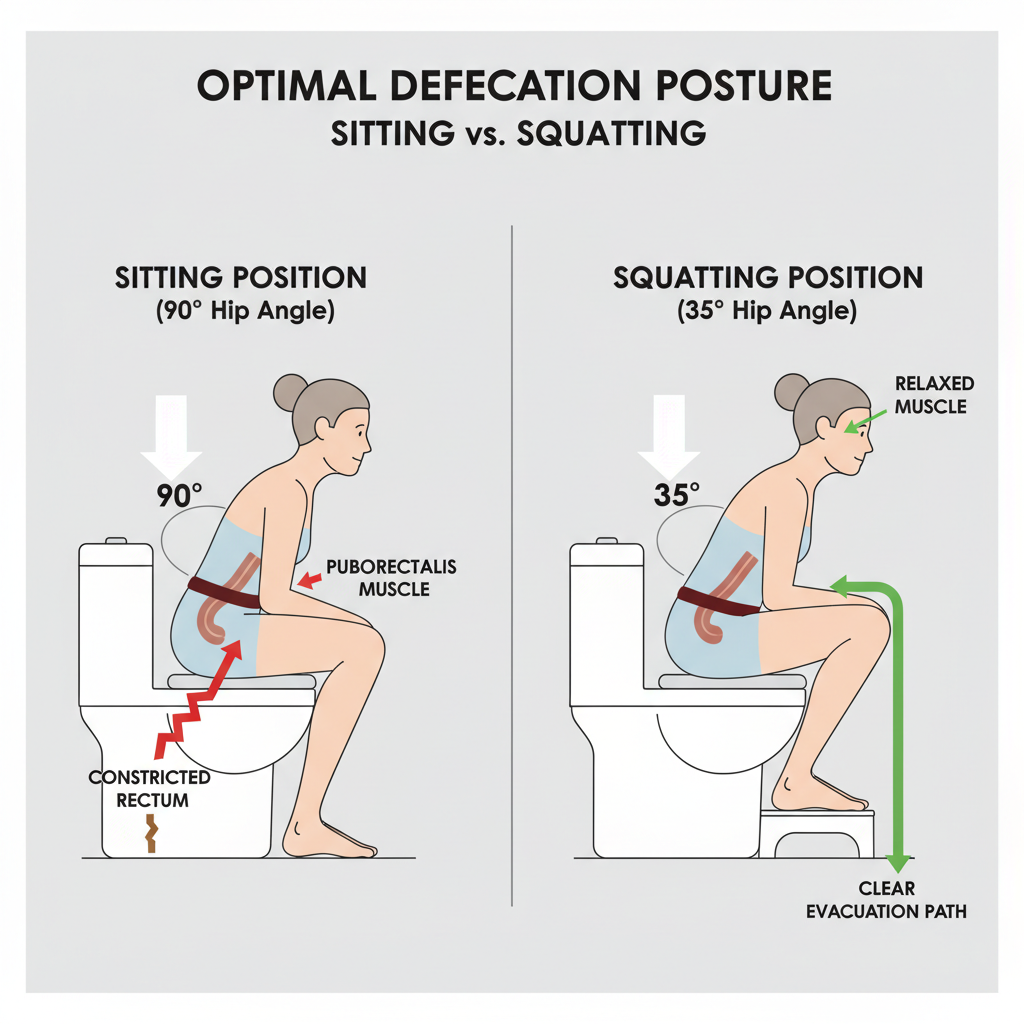

Defecation Posture: The anorectal angle plays a crucial role in elimination. Sitting on a standard toilet creates a $90^{\circ}$ angle, which can partially kink the rectum (via the puborectalis muscle). Squatting (or using a footstool) reduces this angle to approximately $35^{\circ}$, straightening the rectum and facilitating easier passage.

Conclusion:

Constipation Awareness Month 2025 serves as a reminder that digestive health is foundational to overall well-being. By understanding the physics of peristalsis, monitoring stool consistency via the Bristol Stool Scale, and adhering to daily habits that support hydration and microbiome diversity, individuals can maintain optimal gastrointestinal function. If symptoms persist despite lifestyle interventions, consulting a gastroenterologist is critical to rule out organic pathology.